As KRC joins the rest of the United States in observing Black History Month, we thought it would be a good opportunity to talk about some important African American organized labor leaders.

Often, Black Americans’ efforts to bring about positive change are overlooked, and this needs to change.

Isaac Myers (1835-1891)

“I speak today for the colored men of the whole country…when I tell you that all they ask for themselves is a fair chance; that you shall be no worse off by giving them that chance”

Isaac Meyers was a caulker, labor leader and advocate for Black workers in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, Emancipation, and Reconstruction. As a young man, he and several hundred Black colleagues lost their shipyard jobs because of racial discrimination against newly freed former slaves. In response, Meyers and others formed the Chesapeake Marine Railway and Dry Dock Company, the first Black owned dry dock in the southern United States. The shipyard was a success, and provided employment to hundreds of skilled craftsmen who would otherwise have been unemployed due to their race.

Meyers was one of the founding members of the Colored National Labor Union, the first nationwide union representing the interests of colored workers. In an era when many labor unions did not allow Black, Asian, Hispanic, or even many European immigrant workers into their ranks, the CNLU was a major step forward. He was elected president of the CNLU in 1869, resigning in 1872.

Far from finished, Meyers later became the first African American postal inspector, as well as President of the Colored Men’s Association of Baltimore. He also worked to support and raise funds for the Freedman’s Bank, a loan bank whose stated purpose was to provide former slaves with access to capital.

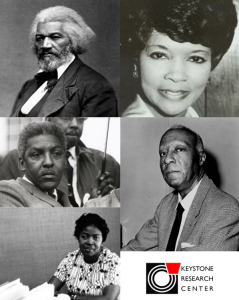

Fredrick Douglass (1818-1895)

“Where justice is denied, where poverty is enforced, where ignorance prevails, and where any one class is made to feel that society is an organized conspiracy to oppress, rob and degrade them, neither persons nor property will be safe.”

Perhaps the most famous entrant on the list, Douglas is often thought of more as an orator, author, and abolitionist, but he was also a strong advocate for labor rights. In the 1850’s, he was named Vice President of the American League of Colored Laborers. After the Civil War and Abolition, Douglas wrote and spoke extensively, encouraging Black workers to unionize and rebuking many labor unions for their refusal to accept African Americans into their ranks. He succeeded Issac Meyers as head of the Colored National Labor Union in 1872, a post which he held until the organization’s dissolution. Between his advocacy and his writing, Douglas’ efforts helped to bridge the gap between the labor movement’s fight for economic equality and the fight for broader racial equality.

Lucy Parsons (1851-1942)

“Never be deceived that the rich will allow you to vote away their wealth.”

Lucy Parsons was a labor organizer and activist who fought for the rights of all workers, but particularly those who were poor, Black, or immigrants. She was a co-founder of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), as well as a member of the Knights of Labor. After her husband, Albert Parsons, was executed in 1887 for his supposed involvement in Chicago’s Haymarket Affair, she became a prominent activist. Fighting for equal rights for workers, fair treatment from tyrannical robber barons, and an end to racial discrimination, Parsons’ legacy greatly influenced those who came after her.

Philip Randolph (1889-1979)

“Those who deplore our militants, who exhort patience in the name of a false peace, are in fact supporting segregation and exploitation”

A pioneering labor and civil rights leader, A. Philip Randolph, led a light at the intersections of equal treatment. He was the President of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first primarily African American industry-specific union to be recognized by a major corporation. The Pullman Company, which was at the time one of the largest employers of African Americans in the country, held a virtual monopoly on the manufacture and operation of sleeping cars in the US. With Randolph’s help in organizing, the BSCP won better protections, higher pay, and opportunities for promotion not before available to Black workers in 1937.

In 1941, Randolph organized the March on Washington with Bayard Rustin. The movement culminated in President Roosevelt issuing Executive Order 8802, which prevented discrimination in the defense industry on the basis of race, color, creed, or origin, and was the first step towards and integrated armed forces. The order also created the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) to enforce the order, which was a direct result of Randolph’s advocacy.

In 1963, Randolph was the chief organizer for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom and stood behind his good friend Martin Luther King Jr. during his famous “I have a dream” speech. In 1964, Randolph stood by while President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act (which he had been consulted during the writing of) into law. Over the next few years, he would receive both the Presidential Medal of Freedom from LBJ and the Pacem in Terris Peace and Freedom Award from Pope John XXIII.

Addie L. Wyatt (1924-2012)

“I knew that I wanted to help other workers, and I found out that I could help them by joining with them and making the union strong and powerful enough to bring about change.”

Addie Wyatt was one of the first African American women to hold a leadership position in a major union, and the first African American woman to be named TIME magazine’s person of the year. After suffering racial discrimination at the canning plant where she worked, she joined the United packing house workers of America. By 1955, she was a full-time staff member of the union. In that capacity, Wyatt was able to help win equal pay for equal work provisions for workers in many canning plants, regardless of their race or gender.

An ordained minister, she and her husband were both members of the southern Christian leadership conference, and worked closely to organize alongside other members, such as Martin Luther King Jr. Like all others on this list Addie Wyatt understood the connection between the struggles of organized labor and the struggles of racial inequity.

In the 1970s she was a founding member of the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists and became a major voice for female workers of all races, religions, and origins. In 1975, TIME magazine named her one of their people of the year for her advocacy against sexual and racial discrimination in hiring, promotion, and pay. As mentioned, she was the first African American woman to receive this award.

Bayard Rustin (1912-1987)

“To be afraid is to behave as though the truth were not true”

Bayard Rustin was a strategist in the labor and civil rights movements. He, along with A. Philip Randolph, organized the 1963 March on Washington. Often shying away from the spotlight, Rustin was deeply involved behind the scenes in organizing for the civil rights movement as well as the labor movement. Rustin was also one of the first openly gay members of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

Ernest Calloway (1909-1989)

“The worker is a ‘Total Person.’ He does not live to work, he works to live, and to live is more than just to survive.”

Ernest Calloway was a labor leader, journalist, and educator who dedicated his life to empowering Black workers. He played a key role in organizing unions within the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) and fought to end workplace discrimination. Calloway also worked to increase political participation among African Americans, organizing voter registration drives and advocating for economic policies that benefited working-class communities. Later in his career, he became a professor, using education as a tool to inspire new generations of activists.

Dorothy Lee Bolden (1923-2005)

“We aren’t Aunt Jemima women. We are politically strong and independent”

Dorothy Bolden was a domestic worker turned labor organizer who fought for the rights of household workers, a group that had long been excluded from standard labor protections. In 1968, she founded the National Domestic Workers Union of America (NDWUA), which organized thousands of Black women to demand better wages, working conditions, and legal protections. She also worked closely with civil rights leaders to mobilize domestic workers as a political force. In addition to labor organizing, Bolden fought against racial segregation and voter suppression, encouraging domestic workers to register to vote and participate in elections. Her work helped bring national attention to the struggles of domestic workers, leading to long-overdue labor protections.