May job numbers for the nation, released June 4, and the Pennsylvania job numbers for April, released late May, deliver a simple message: we have gained back some jobs lost at the outset of the COVID recession, but we still need to create at least 400,000 jobs in Pennsylvania and 10 million nationally. That makes the already enacted American Rescue Plan, including the $300-per-week federal supplement to unemployment insurance, vital not just to people receiving checks but to other workers and to small businesses. This relief maintains consumer buying power and sustains our economic recovery. The current numbers on jobs—and on small business revenues—also suggest we still need additional federal stimulus, including a robust infrastructure package.

Actions that scale back buying power the economy needs for a strong recovery, such as slashing unemployment benefits, hurt not just the workers who lose income—or who are coerced into taking a low-wage job that fails to capitalize on their skills and experience—but other working families and small businesses. That is because cutting unemployment benefits reduces consumer demand and extends joblessness further into the future. As in the “jobless recoveries” of the early 2000s and after the Great Recession, years of slow job growth would mean years of little or no wage growth for middle- and lower-wage workers generally. That is why you get hurt when your neighbors’ unemployment benefits get cut.

What the numbers say

In this section, we take a look at the national job numbers for May and the Pennsylvania job numbers for April. We also look at small business revenues through May 23.

• Nationally, the labor market is still down 7.6 million jobs since February 2020. Taking account of national population growth since that date, the U.S. jobs shortfall is roughly 10 million.

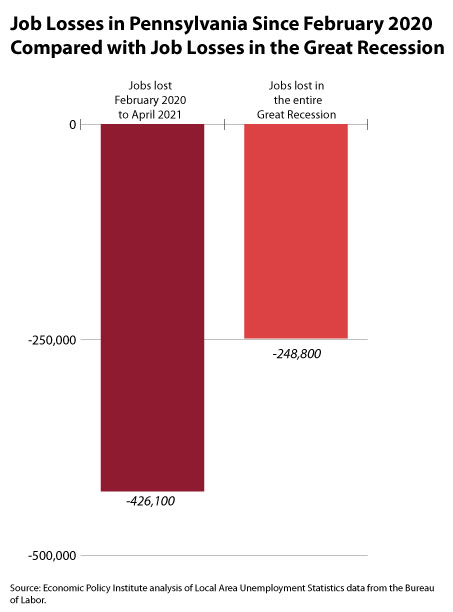

• As of April, Pennsylvania still had 426,100 fewer jobs than in February 2020—i.e., we have lost one of every 12 jobs. That’s nearly 9% of our jobs. If we counted every person who lost a job since February 2020 as unemployed—which we don’t—the unemployment rate in Pennsylvania would be about 13%. As the chart below shows, the 426,100 jobs lost far exceeds job loss in the “Great Recession.”

• The U.S. unemployment rate fell to 5.6% in May; it was still 7.4% in Pennsylvania in April. But since we do not count all people who lost jobs in the pandemic as unemployed, both the U.S. and state unemployment rates at this juncture are deceptively low and give a false sense of how much the economy has recovered.

Turning to small business revenues, the chart below shows that Pennsylvania small business revenues are still about 25% below their level before the pandemic. That’s a bit better than the national decline of nearly one third, but it’s not good. For small businesses as well as workers, especially now that it is safe in most businesses to return to work, it will be a disaster if policymakers take their gas off the accelerator prematurely.

What the numbers mean

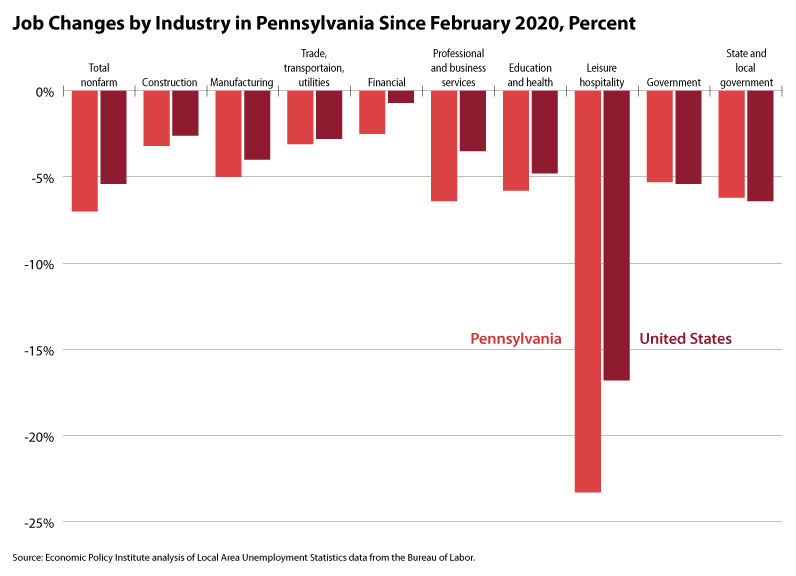

The chart below shows Pennsylvania’s sectoral pattern of job decline since February 2020. By and large, job loss by sector reflects the extent to which different parts of the economy can, or can’t, operate digitally as opposed to in person. Leisure and hospitality show by far the biggest decline in jobs since February 2020, more than one in five jobs in Pennsylvania. Construction, most of which is outside work, has lost only one in 33 jobs. Financial services, much of which can take place digitally, has lost only one in 40 jobs.

What the numbers don’t mean

Since May, conservatives have been claiming that job recovery is being held back by overly generous unemployment benefits. The federal government currently supplements those benefits by $300 per week using funds in the American Rescue Plan. Half of the states, all led by Republicans, have used the argument that unemployment benefits are too generous to justify halting some or all emergency benefits ahead of schedule. Residents of these states will forego an estimated $22 billion in buying power because their lawmakers’ want to play Ebenezer Scrooge. If Pennsylvania did the same, we would forego roughly $2 billion in buying power.

Anyone remember what the $1 billion cut in education spending did to Pennsylvania’s economy in 2011-14?

The evidence does not support the Republican view of what is holding back job growth. Yes, there are help wanted signs in restaurant and store windows. Many businesses have been shut or only offering take-out and now want to open more fully. They have openings to fill, which takes time. Many other businesses, however, including in hospitality industries that cater to business travelers and vacationers, are not yet ready to open or operate at pre-pandemic levels. They do not see the consumer demand to warrant a full opening yet. And some businesses may never re-open and/or may have permanently eliminated positions (e.g., as cashiers in supermarkets). As these examples illustrate, what’s holding back job growth is still the lack of consumer demand.

When it comes to the supply side of the equation—to workers—the primary reason many adults with children are not back to work, or shifting from part-time to full-time, is not a small increase in weekly benefits (which amounts to only 40% of the minimum wage for a full-time worker). The reason is that some schools and childcare providers are still closed or open only part-time. Maybe if the (mostly) rich, old, white male lawmakers eager to slash unemployment benefits knew more working families with children, they would understand this.

Economic research confirms that the Republican narrative about overly generous unemployment benefits is wrong. When the supplement to weekly benefits was twice as big—$600 per week—under the CARES Act signed by President Trump, Yale economists found that expanded jobless benefits did not decrease employment or deter people from returning to work when the economy began to pick up.

Do Republicans like cutting unemployment benefits and keeping wages low…just because?

In the debate about unemployment benefits it might be helpful to remember that the U.S. first established a federal-state partnership to provide unemployment benefits in 1935, when the unemployment rate was 20%. Like other pillars of the 1930s New Deal, unemployment benefits aimed to do two things: help people on the front end of the deepest economic downturn in recorded U.S. economic history AND increase the buying power of families so that consumer demand would kickstart the economy.

The other three pillars of the New Deal also helped specific groups of people AND aimed to boost purchasing power. Social Security, enacted in 1935, lifted seniors out of poverty AND enabled them to buy more. The minimum wage, enacted in 1938, gave low-wage workers a raise AND enabled them to afford more goods and services. The Wagner Act gave workers stronger rights to unionize, leading more manufacturing workers to form unions, raise their wages, AND increase their consumer demand.

After the 1930s, economists described unemployment benefits as an “automatic stabilizer” of the economy. Here is what they meant by this: when unemployment starts to rise, unemployment benefits replace a portion of workers’ wages so that workers and their families can continue making some purchases at local businesses. Thus, unemployment benefits automatically stabilize demand by preventing demand from plunging as much as it would without unemployment insurance.

The big problem with unemployment benefits today in the U.S. is not that they are too high but that they are too low, in part because southern states have made benefits so miserly. In non-recessionary periods—i.e., when the federal government does not supplement state benefits—U.S. unemployment benefits on average now replace less than one of every seven dollars that workers as a group earned on their previous jobs. That’s a very small contribution to stabilizing consumer buying power! (Here’s the calculation behind “less than one of every seven: in 2019, 29% of unemployed U.S. workers received unemployment benefits; in the most generous states benefits replace at best half of prior wages. Half of 29% is 14.5% or about one in seven.)

Since the conservative idea that unemployment benefits could slow the economic recovery holds no water, why do conservatives want to keep wages low? One reason: the corporate interests to which conservatives respond—such as the National Restaurant Association—want to keep wages low. Low benefits that coerce workers into taking bad jobs is one way to do that. Slowing the recovery by cutting working-class buying power is another. Some conservatives may also believe that cutting wages—along with lowering taxes for rich people and corporations—is a good way to boost job growth despite the evidence to the contrary. After this has been part of the conservative narrative since Ronald Reagan was president in the 1980s.

“Build back better” vs. “Build back the same or worse”

In broad terms, the battle over unemployment benefits relates to the overall policy debate at the federal and state levels regarding whether the U.S. can use the pandemic to address the structural inequalities that have characterized our economy over the past 40 years. Cutting unemployment benefits is part and parcel of an approach that would sustain low wages, high inequality, and racial inequity going forward. If you like shared prosperity and reducing racial injustice, then you should support maintaining unemployment benefits—along with other policies that put money in the pockets of working families so that their consumer demand drives the economy forward. If you want more, not fewer, Pennsylvania small businesses that have been hammered in the pandemic to rebound, you should also support maintaining unemployment benefits.